Past

-

A Botanical Future

Katrín Elvarsdóttir Oct 23 - Dec 6, 2025 Gallery Gudmundsdottir is pleased to present A Botanical Future , the first solo exhibition by Icelandic artist Katrín Elvarsdóttir at the gallery. The exhibition brings together three photographic series created between 2020 and 2025: Fifty Plants for Peace , Tropical Colony , and Living Fossil , each exploring the intersections... Read more -

The Rehabilitation of La Casa Invisible

Libia Castro & Olafur Olafsson Sep 4 - Oct 18, 2025 Opening a new chapter of activist art, collective architecture, and civic imagination, Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson, together with La Casa Invisible in Málaga, present The Rehabilitation of La Casa Invisible – Chapter I, an expansive community art project that operates across architecture, film, activism, and social practice. La Casa... Read more -

BeastQuest

Kolbeinn Hugi Jun 13 - Aug 1, 2025 Gallery Gudmundsdottir is pleased to present BeastQuest, a solo exhibition by Icelandic artist Kolbeinn Hugi. Opening on June 13, the exhibition features the premiere of his latest film, BeastQuest, a new chapter in his exploration of the Animal Internet, a speculative networked ecology that reimagines agency, sentience, and communication beyond... Read more -

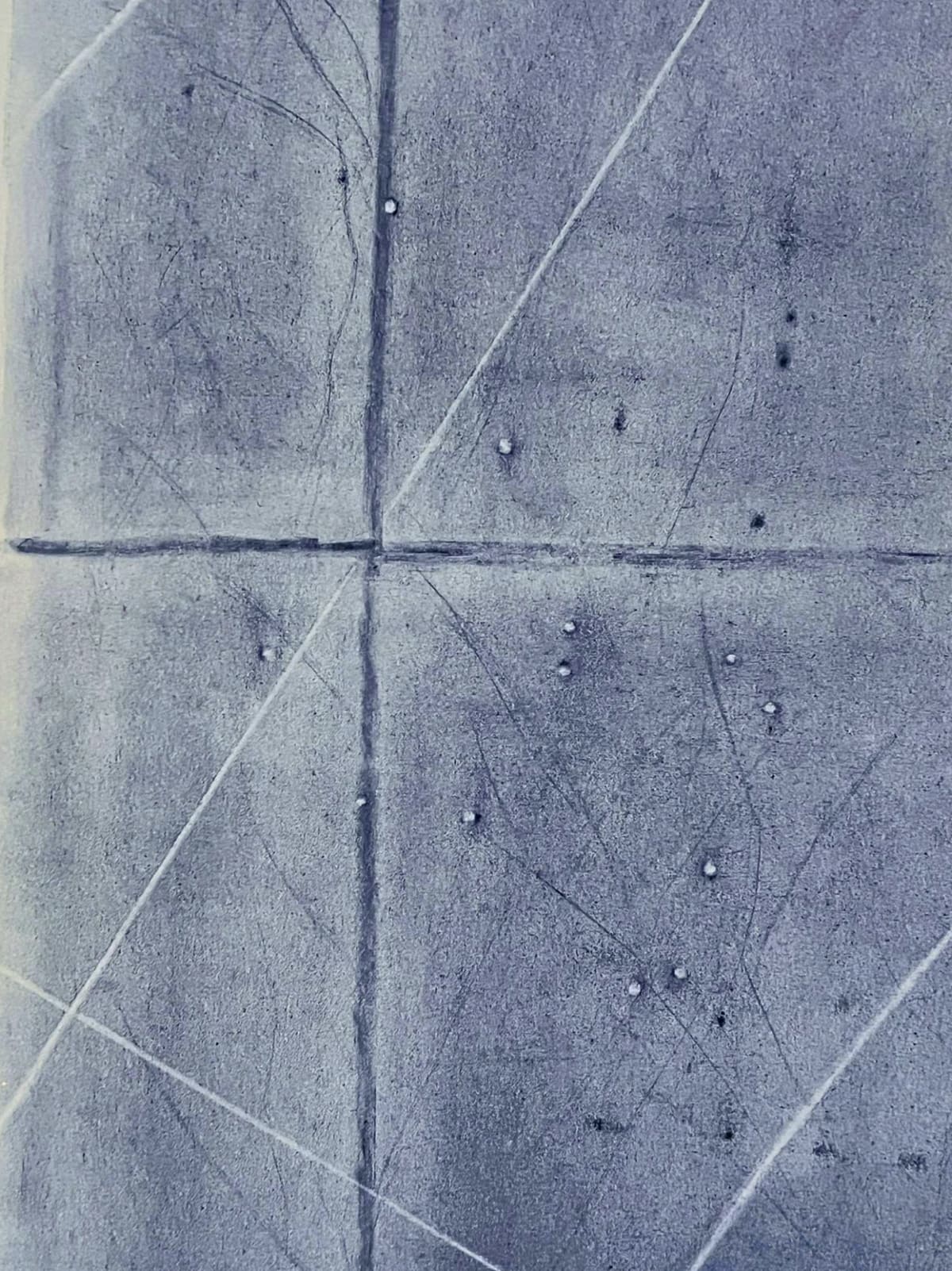

S-I-L-I-C-A-0-2

Hulda Rós Gudnadóttir Apr 4 - Jun 3, 2025 Hulda Rós Gudnadóttir's exhibition S-I-L-I-C-A-0-2 examines the global manufacturing structure behind silicon-a key component in technologies central to green energy transition such as solar cells as well as consumer electronics and our social infrastructure in general. Through sculptures, photographs, and materials from the production process, Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir traces the material's journey from extraction to the creation of purer silicon and beyond, revealing the vast network of industries, landscapes, and geopolitical forces that shape its production. Read more -

The Western Horizon

Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir Jan 16 - Mar 20, 2025 Gallery Gudmundsdottir is proud to present The Western Horizon,

the first solo exhibition by Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir at the gallery, opening on January 17, 2025. This exhibition brings together a collection of recent and new works that Gunnlaugsdóttir describes as a “still life of Western culture,” offering an exploration of contemporary cultural narratives and the tensions that define them. Read more -

JólaBazar

Group Exhibition Dec 18, 2024 - Jan 5, 2025 Jóla Bazar 2024 brings together a selection of contemporary artworks, unique editions, and handcrafted objects presented in a warm and festive atmosphere at Gallery Gudmundsdottir. The exhibition offers visitors an opportunity to discover small-format works and special pieces by the gallery’s artists, thoughtfully curated for the holiday season. Jóla Bazar... Read more -

Ties

Björg Thorsteinsdóttir Nov 7 - Dec 18, 2024 The exhibition Ties presents a curated selection of works by artist Björg Thorsteinsdóttir, created between the 1970s and the 2010s. Featured are her acrylic paintings, graphic prints, and sculptures crafted from Japanese paper. At the heart of this exhibition is Thorsteinsdóttir’s lifelong exploration of geometric form—a theme she pursued across monochrome graphic prints, vibrant canvases, and the layered textures of her paper sculptures. Read more -

Colossos

Anna Sigmond Gudmundsdóttir Sep 7 - Nov 2, 2024 Anna Sigmond Gudmundsdottir's second solo exhibition at Gallery Gudmundsdottir, titled 'Colossus,' opens on September 7, 2024, exhibiting her latest works. The title honors the first programmable electronic digital computer, developed in 1940’s. This choice reflects the relationship between human creativity and the precision of programming. In her works, this connection... Read more -

Your Feelings Matter

Katrín Inga Jun 6 - Jul 20, 2024 “Your Feelings Matter' invites us to delve into the philosophical undercurrents of everyday objects. Through installations and sensory experiences, the exhibition explores chewing gum—a symbol of perfect abstract form. It is not rigid or fixed but dynamic and evolving, much like our thoughts and emotions. Within Gallery Gudmundsdottir, 'Your Feelings... Read more -

Reeling of Disbelief

Ivy Lee Apr 23 - Jun 1, 2024 In On the Heavens, Aristotle described the theory of musica universalis . A metaphysical concept inherited from the Pythagoreans positing that the celestial spheres, from barren moon to atomic sun, even the microbial paradise of Earth, all produce a hum. That ours is a Universe inundated by vibration whose all-encompassing... Read more -

The New Topography of Modern Literature

Malcolm Green Mar 2 - Apr 13, 2024 Gallery Gudmundsdottir is delighted to present 'The New Topography of Modern Literature'' a solo exhibition of Berlin based British artist Malcolm Green, b. 1952. 'The New Topography of Modern Literature” provides an insight to Malcolm Green's body of work, including earlier works from 1976 to the present. With a background... Read more -

Chromatic

Anna Rún Tryggvadóttir Oct 28 - Nov 30, 2023 The exhibition Chromatic by Anna Rún Tryggvadóttir displays a new series of watercolour works and a sculpture stemming from the artist's ongoing research project Multipolar which explores the history of the magnetic field of the Planet. In her praxis Tryggvadóttir explores invisible forces in nature in a quest of furthering... Read more -

Written In Blood

The Icelandic Love Corporation Sep 6 - Oct 28, 2023 Middle-Aged Magic There is no greater power in the world than the zest of a postmenopausal woman. Margaret Mead, 1901-1978 After centuries of medical science, we should think that by now we would have a solid understanding of the female body. We should think that we understand its biology, its... Read more -

My Mother’s Dream

Erla S. Haraldsdóttir Jun 16 - Jul 29, 2023 The unconscious text is already a weave of pure traces, differences in which meaning and force are united—a text nowhere present, consisting of archives which are always already transcriptions. Originary prints. —Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference (1967) In his seminal book Writing and Difference, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida clarifies... Read more -

Cassiopeia

Gudny Gudmundsdóttir Apr 28 - Jun 5, 2023 Compositions, palette, arrows, and text create an architectural first impression, while archaic visual elements reminisce watercolour sketches by those early 20th century spiritists probing communication between the spiritual and material worlds. In Maison de Poseidon – someplace between a drawing, flow chart and score – the lines sometimes resemble structures... Read more -

Don’t Come Crying To Me

Melanie Ubaldo Mar 10 - Apr 15, 2023 In her solo show at Gallery Gudmundsdottir, Icelandic artist Melani Ubaldo takes a deeply intimate look at how immigrant placemaking––or, seeking your place in the world and navigating the dissonance of feeling othered––manifests in its interior, phenomenological dimensions. The show evolves the trajectory of Melanie’s earlier work, which deconstructed overt,... Read more -

Anything Goes

Group Exhibition Nov 4 - 28, 2022 The Christmas Show 2023 brought together a vibrant selection of works by artists connected to the gallery’s extended community. Featuring contributions from Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson, Gudny Gudmundsdottir, Ivy Lee, Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir, Anna Rún Tryggvadóttir, Anna Sigmond Guðmundsdóttir, Anna Júlía Friðbjörnsdóttir, Erla Haraldsdóttir , Kolbeinn Hugi, Katrín Inga... Read more -

Last Season

Anna Júlía Fridbjörnsdóttir Sep 15 - Oct 22, 2022 “. . . out there past men’s knowing, where the stars are drowning and whales ferry their vast souls through the black and seamless sea. Cormac McCarthy The work of Anna Júlía Fridbjörnsdóttir employs diverse mediums and materials to examine contemporary environmental concerns through a poetic perspective, imaginatively reconciling human-based... Read more -

The First Day

Group Exhibition Jul 28 - Sep 28, 2022 “On the first day, God created light in the darkness.” Genesis stories are a part of virtually every culture, with human imagination aiming to solve the mysteries of the creation of our world and existence, seeking to give direction and meaning to our lives. The theme of light is ever... Read more -

Top Tier

Kolbeinn Hugi Jun 10 - Jul 24, 2022 When Zoocrazy arrived, it had already been years in the making: by the mid 21st century the idea of the Anthropocene directed all efforts of emotional and environmental empathy, but what was missing was everyone else. People shook their heads at anthropomorphism. They hunted, farmed, or kept everyone on a... Read more -

Three Norths

Anna Rún Tryggvadóttir Apr 30, 2022 - Jun 3, 2023 Three Norths , Icelandic artist Anna Rún Tryggvadóttir’s solo exhibition opening at Gallery Gudmundsdottir on April 29, 2022 is a meditative exploration of intersections between nature, materiality, temporality, and artistic process.Tryggvadóttir’s pieces range from experiments with organic pigments and magnetic rocks to playful interventions in natural environments. They are designed... Read more -

Landscape Enclosed

Anna Sigmond Gudmundsdóttir Mar 19 - Apr 24, 2022 Icelandic-Norwegian artist Anna Marie Sigmond Gudmundsdottir is renowned in both Iceland and Norway for her multimedia drawings, paintings, installations, and public murals. Her solo exhibition Landscape Enclosed , opening at Gallery Gudmundsdottir in March 2022 showcases her characteristic attention to disciplined line work: each line in her large-scale pieces is... Read more -

In Search Of Magic – A Proposal for a New Constitution

Libia castro & Olafur Olafsson Nov 26, 2021 - Apr 2, 2022 Gallery Gudmundsdottir proudly presents the exhibition and ongoing project In Search of Magic – A Proposal for a New Constitution for The Republic of Iceland by the Spanish-Icelandic artist duo Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson together with the elastic artist-and-activist collective The Magic Team. For this work the artists received... Read more -

WERK

Hulda rós Gudnadóttir Sep 16 - Oct 23, 2021 Cool, sober, crisp and clean, the photographs by Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir are at first look graphic studies of light, shadow, seriality and rhythm. On closer look it becomes clear that these mid-scale photographs, wrapped in sleek frames of the palest blue, depict white shipping boxes with royal blue lettering, stacked... Read more -

IONIZER

Ivy Lee Jul 23 - Sep 1, 2021 The first solo exhibition by Ivy Lee (1992, Berlin) explores a dialectic between romantic visions of immersion within nature and modern attempts to recuperate such values through the deployment of new technologies. Trained in architecture and urban design, Ivy Lee approaches atmosphere through the dual lenses of ambience and air... Read more -

Land Self Love

Katrín Inga Sep 11, 2020 - Jul 21, 2021 In the exhibition Land Self Love, artist Katrín Inga Jónsdóttir Hjördísardóttir explores the trajectories of love, ownership and self-expression through her own physicality, in a quest of finding balance between her Eros and Thanatos. Her journey becomes a physical expedition through the territory of the love within. Her approach to... Read more -

Cold Man’s Trophies | Pure Maid’s Garlands

Gudny Gudmundsdóttir Jul 31 - Sep 5, 2020 In fluid dynamics, a vortex is a region in liquid in which the flow revolves around an axis line; it may be straight or curved. The concept of circulation exceeds our sensation of time as if stuck, placed, compartmentalised in vertical vacuum without linear time. Our perception of an endless... Read more